Senior VP Kurt Knaus analyzes the upcoming debates state officials will have on thorny topics from COVID to the budget to handling this fall’s elections.

Pennsylvania lawmakers began the second half of the two-year legislative session earlier this month, and their plates are full of unfinished business.

That doesn’t mean, however, that they didn’t accomplish anything over the last 12 months.

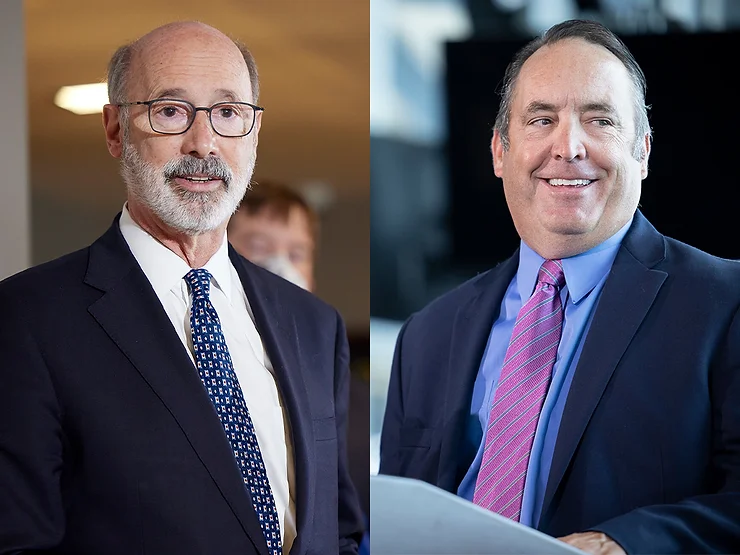

In fact, in year-in-review messages from the administration and legislative caucuses, Gov. Tom Wolf boasted about improving schools, creating jobs and expanding health care; Democrats claimed they delivered for families, communities and the environment; and Republicans trumpeted successes in pandemic relief, regulatory reform, crime prevention and the economy.

By those accounts, from the outside looking in, Harrisburg looks like an institution of supreme efficiency and bipartisanship, where political foes set aside differences and churn out policy proposal after policy proposal to bolster the commonwealth and uplift its residents.

That’s hardly the reality. Pennsylvania’s opposing parties are locked in trench warfare.

State government is more divided than ever — and not just between the Democratic administration and Republic-controlled General Assembly, but within the caucuses as well. Partisans on the left and right want control of their parties.

Most bills never get a vote, let alone get enacted. Some that pass get vetoed. Wolf already has penned more than 50 vetoes, more than any governor since 1979, and he still has a full year in office.

That’s the anomaly of Harrisburg.

The flurry of activity residents view or read about is usually just a kneejerk reaction to some chatter call or a quick strike from a partisan playbook — a lot of movement, but little real advancement.

That doesn’t mean there isn’t compromise. There is. You just have to look hard to find it.

How this new year ultimately ends up is anyone’s guess. The next batch of year-in-review messages will write themselves, depending on what happens in the November general election. But here are a few things to watch for in coming months:

COVID-19

The pandemic is not finished. The dizzying speed of omicron’s spread has left everyone scratching their heads and questioning what they know about COVID-19. To mask (by mandate) or not to mask? How long should a sick or an exposed person quarantine? And why can’t anyone find a testing kit?

A few things are certain: Pennsylvania will try to legislate its way out of the pandemic by revising its constitution. Residents won’t tolerate another shutdown. Parents want their kids in school, no matter what, and healthcare workers deserve every accolade they can get, especially from the unvaccinated.

Fortunately, unlike in previous variants, the loss of taste and smell seem to be uncommon in omicron. That’s good, because this whole thing stinks.

2022-23 State Budget

Structural deficits. Fiscal cliffs. Budget shortfalls. A collapsing economy. It’s not science fiction. That was Pennsylvania’s reality just a few years ago — and there is still some truth behind the numbers, given how the state camouflages its finances with budget gimmicks and fund transfers.

But this year — an election year, a big election year — is different.

The governor will give his annual budget address Feb. 8, and he’s already off to a good start. The state has collected $22.6 billion in the current fiscal year, seven percent ahead of projections. Pennsylvania still has at least $5 billion in unspent federal recovery funds squirreled away to allocate toward the 2022-23 budget, a fact that has upset many constituencies still trying to recover from the pandemic.

While the numbers look strong, there remain risks to the economy: inflation, a clogged supply chain, and a shortage of workers. Also, it’s an election year, a big election year. (Did we mention that?) Republicans will not give the governor or Democrats any big budget wins, but they will craft a spending plan that betters their own election odds.

Pennsylvania’s Primary

Every 10 years, the U.S. Constitution requires a count of all people living in the United States. That decennial census gives elected leaders the data they need to make smart decisions about how to fund community needs. But that count is also important to ensure fair political representation.

Last month, Pennsylvanians got a look at the first drafts of the new congressional and state legislative maps that will define the districts to take effect in the 2022 election cycle. Now they must review the drafts and submit comments so lawmakers can adjust the final maps. That takes time, and the deadline it tight.

The Pennsylvania Department of State told the legislature that it must finalize the maps by Jan. 24 to allow time for candidates to circulate nominating petitions ahead of next year’s May 17 primary.

Right now, there’s no consensus on whether to push it back a month or forge ahead.

Election Reform

No matter when the primary is held, how Pennsylvanians vote and how the state administers its elections are still open questions.

Republicans in both the House and Senate continue to push comprehensive — and some would say partisan — election reform proposals. The Senate plan has yet to clear the committee hurdle. The House plan is ready to go, although the governor already vetoed a nearly identical version of the House package last June.

How this debate plays out could affect the outcomes of races up and down the ballot.

2022 Elections

Did we mention it’s an election year? A big election year?

Gov. Tom Wolf is finishing his final year in office because of term limits. Voters will decide who’s on deck to lead the commonwealth’s executive branch, and some of the candidates are current General Assembly members.

All 203 members of the Pennsylvania House of Representatives face re-election. Half of the state’s 50 senators also go before voters.

If that isn’t enough, voters will elect a replacement for retiring Republican U.S. Sen. Pat Toomey. The outcome could decide which party controls the U.S. Senate.

Because of population changes, Pennsylvania will lose one congressional seat in the 2022 election cycle, dropping from 18 to 17 seats. The state’s congressional delegation is now split evenly among nine Republicans and nine Democrats, but all that is about to change, with the change affecting control of Congress.

There’s a reason Pennsylvania is called the Keystone State.

Kurt Knaus is a Senior Vice President at Ceisler Media’s Harrisburg office.